14. August 2025

Imperfection as an alternative: Why less perfection leads to more innovation

In our mini-series, AI @ Work, we explore how artificial intelligence is transforming the world of work and the ways in which we, as humans, are responding to this change. Having examined the cognitive and social effects, we now shift our focus to a change of perspective.

In a world striving for digital perfection, the courage to embrace imperfection is proving to be the key to real progress. This article explores how embracing imperfection as an alternative to overly perfected AI solutions can open up new avenues for innovation and human connection.

The AI revolution and its daily updates

Almost every day, companies are launching new AI models or releasing updates to existing ones: Examples include LLAMA 3.2, Claude 3.5 and ChatGPT 4o. There is an AI model for every purpose.

Need a digital assistant? Pi.ai provides a socially intelligent one. Need faster programming? GitHub Copilot takes care of code optimisation. However, the widespread use of these models raises the same question: Are AI tools alienating us from the real world, and if so, what could be the alternative?

A critical examination

Is AI too perfect?

From today's perspective, the answer to this question is clearly 'no'. AI models tend to fantasise, inventing things that do not exist and forcing users to constantly question the information they receive. Image generators are not error-free either. However, the truth is that AI model development is exponential. Five years ago, the idea of having emails or templates created by a chatbot would have been unthinkable. Back then, chatbots could only link keywords to help articles, and not very effectively. Today, there are bots with API connections to almost every LLM, which can be used individually, automatically, and in the appropriate voice.

The speed of this development raises fundamental questions: If AI systems are improving all the time, even surpassing human capabilities, what implications does that have for our creativity and how we handle mistakes? The answer may lie in a conscious counter-model.

In figures

The unstoppable growth of artificial intelligence

Private investment in artificial intelligence development amounted to 5.17 billion US dollars in 2013, peaking at 132.36 billion dollars in 2021 (source: Stanford AI Index Report). Although less money flowed in 2022 and 2023, with investments totalling 103.4 and 95.99 billion dollars respectively, private investment remains at a high level. Market researchers at MarketsandMarkets estimate that AI revenue will reach 407 billion US dollars by 2027.

These enormous sums of investment show that the industry is focusing on perfection and optimisation. However, there is also a growing awareness of the downsides of this development, and a longing for authentic, imperfect experiences.

The dark side of perfection

Impact on self-perception

In 2017, the French National Assembly passed Décret n° 2017-738 du 4 mai 2017 relatif aux photographies à usage commercial de mannequins. In English: ‘Decree No. 2017-738 of 4 May 2017 on photographs of models for commercial purposes.’

Behind this unwieldy name lies a law that became famous in the media as the ‘Photoshop law.’ Since then, images of models that are published and have undergone some form of manipulative image editing must visibly bear the note ‘Photographie retouchée’ – in English: ‘Image has been retouched.’

Politicians recognised a worrying trend: young people feel bad because they cannot live up to the unrealistic beauty ideals presented in advertising posters – no matter how hard they try.

The scientific facts speak for themselves.

A meta-analysis by Saiphoo and Vahedi (2019), which involved over 36,000 participants, shows that heavily edited images, in particular, contribute significantly to body image problems and increase the risk of eating disorders. Further studies confirm this for images on social media. A 2023 study by the Bulimia Project revealed significant similarities between AI-generated images and retouched images in terms of their impact on self-perception. 40% of AI-generated 'ideal body images' displayed unrealistic body proportions. Nevertheless, comprehensive long-term studies on the impact of AI content on the psyche are lacking.

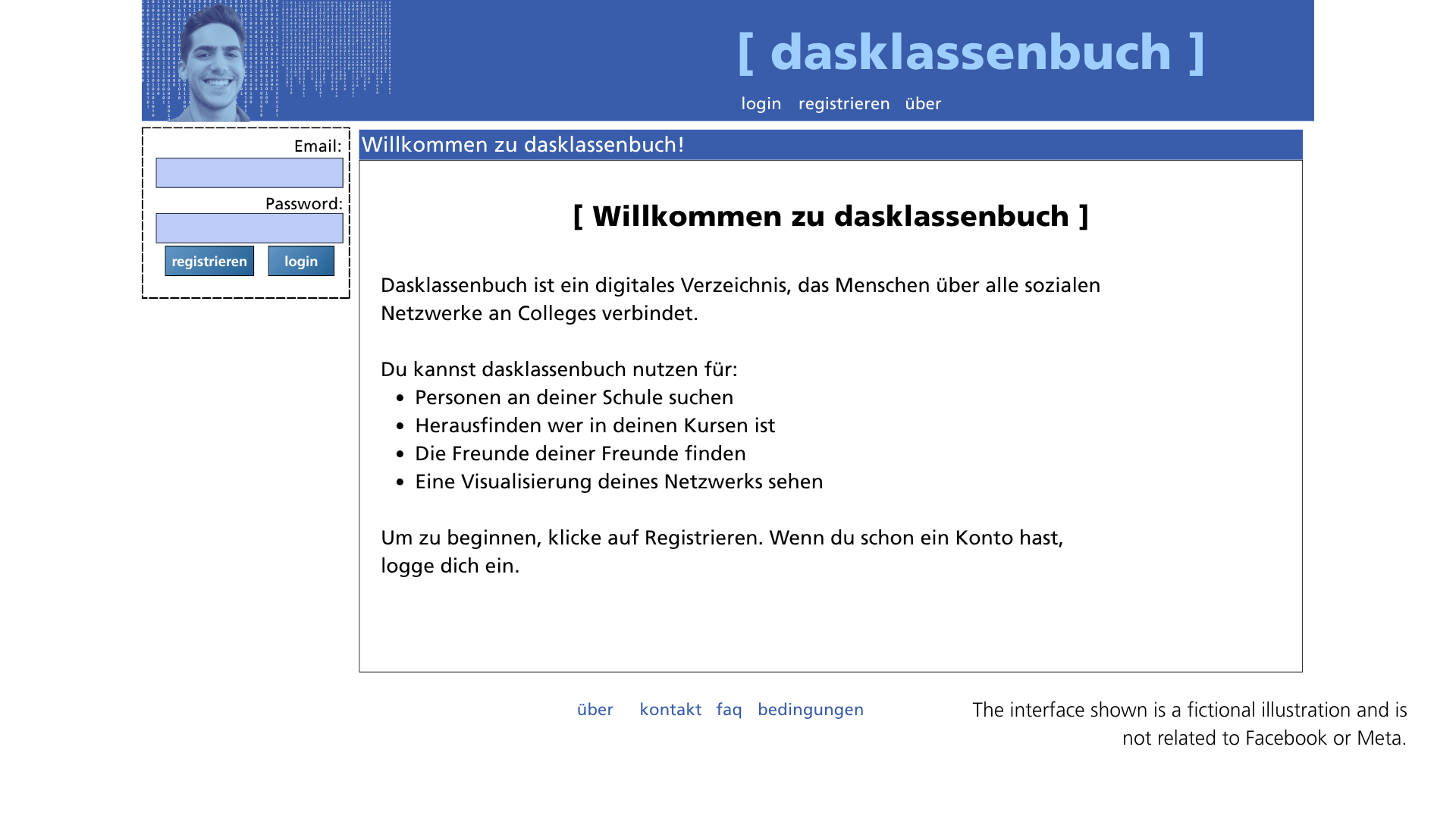

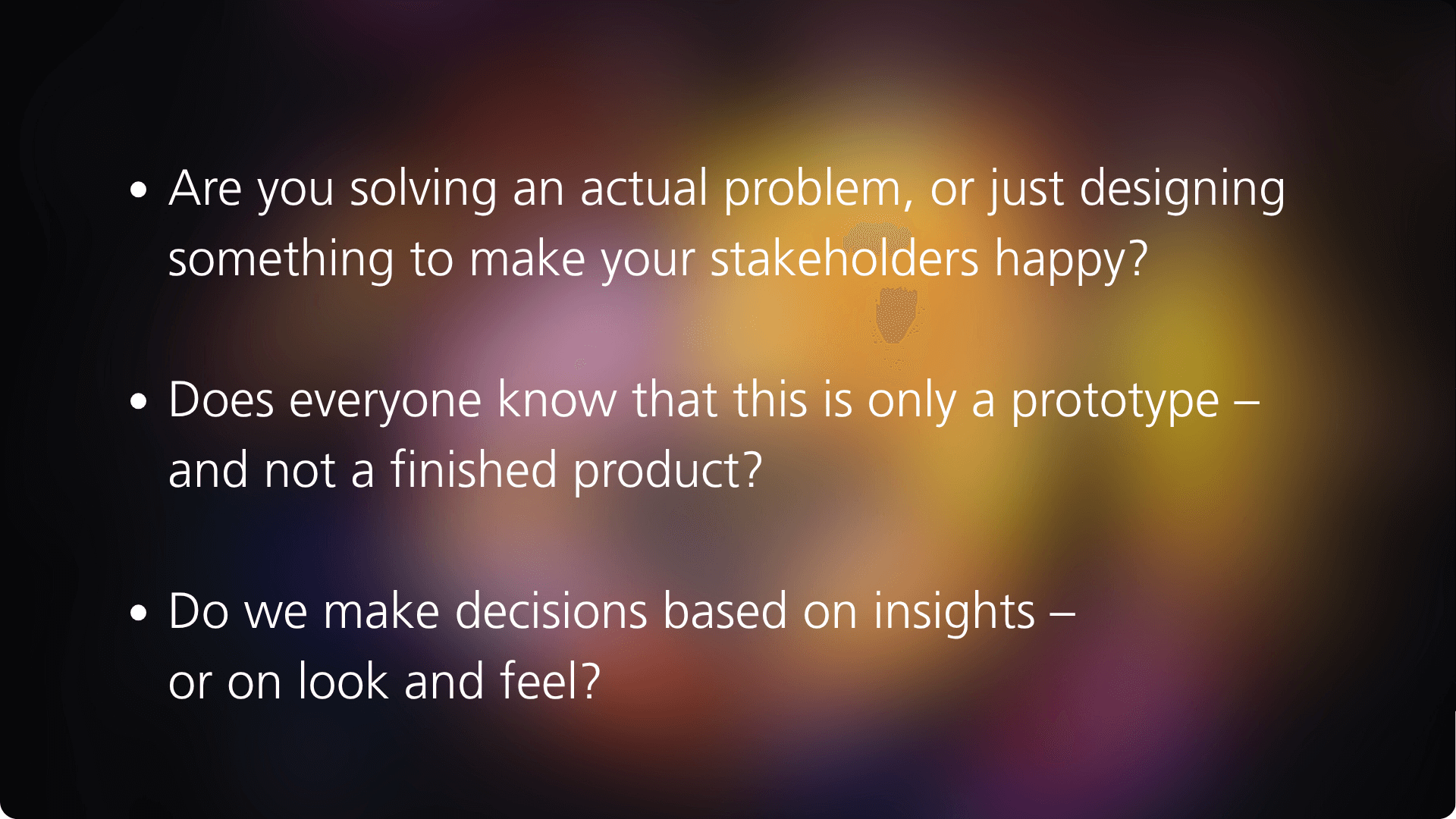

The 'Pretty Prototype Dilemma': getting things not done

A similar phenomenon in the technology sector slows down innovation: the 'pretty prototype' dilemma. Many developers and teams withhold prototypes and minimum viable products (MVPs) because they supposedly don't look good enough. This can lead to delays in development and, in the worst case, failure, because too much time is spent on design at an early stage.

This is not about the overall design, but rather excessive perfectionism. Concerns that an application is not attractive enough result in significant delays and unnecessary consumption of resources at the prototype development stage.

Studies show that around 70% of start-ups fail not because of bad ideas, but because they launch too late. The perfectionism trap is particularly prevalent among tech-savvy founders who want to optimise every line of code before showcasing their product. According to current data, 90% of start-ups ultimately fail, with the most critical phase being years two to five – precisely when many are still working on the 'perfect' version instead of gathering feedback.

The revolutionary alternative

Imperfection as a strategy

The body care brand Dove, for example, launched its ‘Campaign for Real Beauty’ back in 2004, focusing on real women of different body shapes, ethnic backgrounds and age groups. And Dove is not alone. The sports company Nike attracted attention with its Imperfection campaigns. The luxury fashion group Gucci also advertised with people who did not conform to the typical beauty ideal of advertising (documentary in Vogue).

The lean startup revolution

In his 2011 book ‘The Lean Startup,’ Eric Ries already noted that avoiding over-perfection and releasing applications early leads to faster feedback, which in turn leads to product improvements. Statistics from Embroker suggest that startups that release MVPs early and implement user feedback promptly have a 30% higher chance of success. Empirical case studies show that launching an MVP early and consistently incorporating user feedback significantly increases the chances of achieving product-market fit and long-term success.

Harvard Business Review warns that many startups neglect a crucial step in the lean startup process—researching customer needs before testing the product. Instead, they rush fully functional products to market too early—often with disastrous consequences if the market does not need the solution.

Over-perfectionism can also lead to 'paralysis by analysis', whereby a person becomes unable to make a decision due to over-analysis. Existing market opportunities are lost because products are realised too late, or not at all.

The courage to be less perfectionist leads to quick and dirty success stories.

There are many prominent examples of companies and former start-ups that have successfully managed to avoid this dilemma.

The neurological basis

Beauty in imperfection

Wabi-sabi, the concept of perceiving beauty, is closely linked to Zen Buddhism and is explained in detail at Japan House London. It is also linked to kintsugi, or gold repair. Bowls are broken and then repaired using urushi lacquer, putty, and gold powder. The result is bowls that are imperfect yet aesthetically pleasing.

Why do our brains love imperfection?

Imperfect things stick in our memory. It is the crack in the wall that attracts our attention. The human brain is designed to latch onto imperfections, generate stronger reactions to them, and thus create lasting memories (research by Stanford University on attention). These reactions can range from surprise and curiosity to frustration. What remains is an emotional connection.

Neuroscientific studies show that our brains are evolutionarily programmed to notice deviations and irregularities. This 'anomaly detection' was essential for survival, and today imperfection is a powerful tool for capturing attention and creating memories.

Mistakes and failure as drivers of innovation

A space that does not allow for mistakes and is geared towards perfection will fail. No room for mistakes means no room for innovation.

The Penicillin Revolution: How a Mistake Saved Millions of Lives

In 1928, Alexander Fleming was conducting research on staphylococcus bacteria. Before going on holiday, he left some Petri dishes containing bacterial cultures in his laboratory (see original paper in the British Journal of Experimental Pathology). When he returned, he noticed that mould had spread through the dishes. Nothing unusual there, but Fleming noticed that there was a zone around the mould where the bacteria he was researching had not settled. This oversight led to the discovery of penicillin, and subsequently to the development of antibiotics, which have since become an indispensable part of medicine.

The microwave: from melted chocolate bars to a kitchen revolution

In 1945, an engineer named Percy Spencer was researching radar technology for detecting aircraft during the Second World War, specifically high-frequency devices such as the magnetron (documentation in Popular Mechanics). One day, he noticed that the magnetron's radiation had melted the chocolate bar in his trouser pocket. This marked the beginning of the microwave's discovery.

Carelessness, mistakes, inaccuracies and imperfections are the main drivers of innovation. You either accidentally discover new things through mistakes, come up with new ideas or learn something new, taking a step forward in development.

The best of both worlds

Using AI to create a prototype

However, aside from the issue of perfectionism, AI offers something exciting: language models make it possible to create a prototype with minimal effort and without the need for in-depth programming knowledge.

The advantages of AI-supported prototype development are clear.

AI tools democratise product development. Where teams of developers were once necessary, individuals with a good idea can now quickly create functional prototypes. The key is finding the right balance between AI support and deliberate imperfection.

- Speed: Go from idea to first prototype in hours instead of weeks.

- Low barriers to entry: No years of programming experience necessary.

- Iterative improvement: Rapid testing and adaptation possible.

- Focus on core functions: AI takes care of boilerplate code while humans concentrate on innovation.

Here is a practical example from the creative industry: Ströer's Creative Analyzer.

The development of the Creative Analyzer by the strategy and innovation team at Ströer is a perfect example of overcoming the ‘pretty prototype dilemma’. Rather than spending months fine-tuning a perfect version, the tool was launched early and has been continuously developed in line with the 'imperfection' approach.

The story behind its creation shows that the team resisted the temptation to develop the ‘perfect’ AI solution straight away. Instead, they quickly brought a functional prototype to market, one of the first tools of its kind. This deliberate imperfection enabled them to gather feedback early on and improve the tool gradually. Today, the Creative Analyzer is constantly being developed based on real user experiences rather than theoretical assumptions.

The result of this bold approach is a tool that is technologically innovative and effective in practice. The successful Mövenpick campaign is just one example of how an 'imperfect' start can lead to real innovation. You can find more details about this groundbreaking approach in the Ströer blog article.

Thus, the Creative Analyzer proves that those who overcome the 'pretty prototype dilemma' and launch early can begin working on further development while others are still fine-tuning perfection.

Conclusion

The future belongs to conscious imperfection

In a world that is becoming increasingly characterised by algorithmic perfection, embracing imperfection can be a way to stand out. Companies that embrace imperfection can forge genuine connections with their users. The challenge lies in striking the right balance: using AI tools to speed up processes while leaving room for human creativity, mistakes and surprises.

The most successful products of the future will probably be those that combine the efficiency of AI with the authenticity of imperfection. Ultimately, people are not looking for perfect machines, but genuine connections and experiences, with all their wonderful imperfections.

Some of the media content in this blog post was created using artificial intelligence (AI).

References

106 must-know startup statistics for 2025. (2020, February 2). Embroker. www.embroker.com/blog/startup-statistics/

Blitz, M. (2016, February 24). Who invented the microwave, and how? Well, it started with an accident. Popular Mechanics. www.popularmechanics.com/technology/gadgets/a19567/how-the-microwave-was-invented-by-accident/

Brynjolfsson, E., & Perrault, R. (n.d.). AI Index. Stanford.edu. Retrieved July 29, 2025, from hai.stanford.edu/ai-index

Grabe, S., Ward, L. M., & Hyde, J. S. (2008). The role of the media in body image concerns among women: a meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychological Bulletin, 134(3), 460–476. doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.460

Grassini, S., & Koivisto, M. (2024). Understanding how personality traits, experiences, and attitudes shape negative bias toward AI-generated artworks. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 4113. doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-54294-4

Hamburger, E. (2014, August 12). Slack is killing email. The Verge. www.theverge.com/2014/8/12/5991005/slack-is-killing-email-yes-really

Harvard business review - ideas and advice for leaders. (n.d.). Harvard Business Review. Retrieved July 29, 2025, from hbr.org

Harvard Business Review (2021) „Why start-ups fail“, 1 Mai. Verfügbar unter: https://hbr.org/2021/05/why-start-ups-fail

Hundreds Register for New Facebook Website. (n.d.). Thecrimson.com. Retrieved July 29, 2025, from www.thecrimson.com/article/2004/2/9/hundreds-register-for-new-facebook-website/

Kotashev, K. (2024). Startup Failure Rate: How Many Startups Fail and Why in 2024? failory. https://www.failory.com/blog/startup-failure-rate

Khanna, D., Nguyen-Duc, A. und Wang, X. (2018) „From MVPs to pivots: a hypothesis-driven journey of two software startups“, arXiv [cs.SE]. Verfügbar unter: arxiv.org/abs/1808.05630.

Lang, S. (2024, February 9). Famous or not, the consequences of AI-generated images are already here for women. Capsule NZ. capsulenz.com/think/impact-of-ai-generated-images/

MarketsandMarkets - revenue impact & advisory company. (n.d.). MarketsandMarkets. Retrieved July 29, 2025, from www.marketsandmarkets.com

Introducing Nike Well Collective: How Nike supports body, mind and life (ohne Datum) Nike.com. Verfügbar unter: about.nike.com/en/newsroom/releases/nike-well-collective

Ries, E. (2011). The lean Startup: How constant innovation creates radically successful businesses. Portfolio Penguin.

Saiphoo, A. N., & Vahedi, Z. (2019). A meta-analytic review of the relationship between social media use and body image disturbance. Computers in Human Behavior, 101, 259–275. doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.07.028

Schilling, J. (2025, May 21). Wenn Kreation auf KI trifft: Mövenpick überzeugt im Creative Analyzer. Stroeer.de. blog.stroeer.de/creation/wenn-kreation-auf-ki-trifft-moevenpick-ueberzeugt-im-creative-analyzer/

Siegler, M. G. (2010, September 21). Distilled from Burbn, Instagram makes quick beautiful photos social (preview). TechCrunch. techcrunch.com/2010/09/20/instagram/

Startup failure statistics: Why do they fail? (2024). (2024, April 14). Llc-New. https://www.llc.org/startup-failure-rate-statistics/

Santangelo, V. und Macaluso, E. (2013) „Visual salience improves spatial working memory via enhanced parieto-temporal functional connectivity“, The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 33(9), S. 4110–4117. Verfügbar unter: https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4138-12.2013.

Sheng, J. u. a. (2025) „Top-down attention and Alzheimer’s pathology affect cortical selectivity during learning, influencing episodic memory in older adults“, Science advances, 11(24), S. eads4206. Verfügbar unter: doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.ads4206.

(N.d.-a). Dove.com. Retrieved July 29, 2025, from www.dove.com/us/en/campaigns/purpose/real-beauty-pledge.html

Marani, F. (2021) The Gucci Beauty tales • Catherine Servel, Vogue. Verfügbar unter: www.vogue.com/article/the-gucci-beauty-tales-catherine-servel (Zugegriffen: 12. August 2025).

(N.d.-c). Businessinsider.com. Retrieved July 29, 2025, from www.businessinsider.com/how-airbnb-started

Kintsugi: Japanese repair technique – (2023) Japan House London. Verfügbar unter: www.japanhouselondon.uk/read-and-watch/kintsugi/ (Zugegriffen: 12. August 2025).

(N.d.-e). Nih.gov. Retrieved July 29, 2025, from pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2048009/

(N.d.-f). Gouv.Fr. Retrieved July 29, 2025, from www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000034580217.