06. August 2025

Humans & AI: a dream team?

Artificial intelligence is changing the way we work – and it's happening now. But what does that mean for us as people, as creative minds, as businesses? In this mini-series, we tackle the topic of AI without resorting to technological hype or science fiction scenarios. Instead, we address the critical questions of our current era.

- Working with AI undoubtedly affects the way we think, feel and make decisions.

- We must retain our creativity and humanity in a world that strives for algorithmic perfection.

- It is clear what will happen to our digital infrastructures when search engines themselves become answer providers.

In three articles, we provide definitive answers to these questions from psychological, cultural and economic perspectives. The series kicks off with a comprehensive exploration of the cognitive and social implications of AI in the workplace. The second part presents an alternative approach: the conscious break with perfection as a path to greater innovation. Finally, we turn to the systemic upheavals in the digital space – from traffic losses to the shift in power on the web.

This series is an invitation to pause: to think faster, more efficiently and more automatically – but more consciously, more critically and more humanely.

Between hype and dystopia

When our team curates the most interesting news from the media, technology and entertainment industries for our weekly newsletter, the artificial intelligence category is always full of all kinds of headlines. This can make your head spin, particularly when studies don't just discuss the positive effects. With tools such as OpenAI's ChatGPT becoming ubiquitous, our language is also beginning to standardise. Suddenly, we all sound the same, and regional dialects and linguistic nuances are in danger of disappearing. Is this a cultural loss?

It's not just our language that is changing, but our interpersonal relationships too. Or rather, our ability to form them: Artificial intelligence has long been more than just an extremely eloquent, seemingly omniscient contact for questions of knowledge. Because ChatGPT, Replika and Character.AI present themselves in such an eloquent way, people also seek emotional support, closeness and validation from them. The machine is always available, never gets annoyed and is always responsive. We quickly become dependent on these advantages, and ultimately, corporations that want to make money from it benefit from this dependency.

Last but not least, the working population is preoccupied with the big question: if AI automates my job, how will I earn a living? It is reassuring to know that major disruptions within occupational groups have been caused by technological leaps in the past – consider the introduction of the printing press and, later, the computer. Nevertheless, frequent announcements by companies regarding automation and job cuts are cause for concern.

Some people are also saying: No, AI will not replace humans. In the future, humans will be replaced by other humans who excel at working with artificial intelligence. This raises another important question:

Will artificial intelligence level the playing field for everyone?

Those who are skilled at prompting can have professional texts written in seconds, develop their first app with Vibe Coding and create stunning visual landscapes. Tasks that previously required years of expertise from copywriters, developers or illustrators now require little or no time investment. Even amateurs can produce acceptable results, as a Stanford University study has confirmed. Inexperienced customer service representatives have experienced a significant increase in productivity thanks to Gen AI, whereas experienced professionals have only seen marginal improvements in their work processes and results.

So far, so good. However, conflicting evidence now suggests that other groups are the real winners in the race for generative AI. In a field experiment conducted by UC Berkeley, Kenyan entrepreneurs used a GPT-based business coach via WhatsApp. The results were very different: high-performing founders increased their sales by up to 20% by using AI strategically to overcome challenges such as power outages. Less experienced entrepreneurs, on the other hand, mainly used AI for additional customer communication and actually recorded an average sales decline of 8%.

So, will the playing field remain uneven? Don't these findings demonstrate that, while AI offers a variety of possibilities, humans still require expertise to collaborate with it effectively and curate its applications?

Can we therefore conclude that automation and augmentation enhance the skills of experts? Does artificial intelligence lead to exponential ‘wealth growth’? In other words, does AI empower people based on their level of expertise?

However, we do know that higher productivity does not automatically lead to greater satisfaction or relief for either laypeople or professionals, especially when pressure to work faster increases.

Even where AI makes us more productive, one question remains: How reliable is the information it provides? How objective and fair is it? And where are its limits?

Why we think AI is smarter than it (currently) is

It is convincingly authentic and eloquent, and it can take on almost any role we want. However, research indicates that we still have a long way to go in developing AI systems and in the way we interact with them. Before we can trust an LLM, we must ask: Does it reflect our world, or can it improve it?

A stochastic parrot: How AI holds up the algorithmic mirror to us

The impact of training data on LLMs' output is nothing new. Nevertheless, this does not seem to affect certain narratives surrounding artificial intelligence. People still like to claim that AI must be ‘better’ than us. In fact, AI reproduces the same biases because it has been trained using the same prejudiced and biased structures with which we humans are confronted every day.

So is it any surprise that studies such as those conducted by THWS show that AI-supported assistance systems exhibit these very same systematic gender biases in everyday situations? In one experiment, for example, artificial intelligence consistently recommended lower salaries to women than to men in negotiation scenarios, despite all other conditions being equal.

This is just one example of many use cases. Therefore, the idea of completely neutral and fair decisions being made by an objective algorithm is still far from being realised.

In addition, AI agents are now entering the workplace. Here, too, it is not always clear where the limits of these new colleagues lie.

Through thick and thin: Is AI mankind's best friend?

Stress in the workplace is a familiar concept to human employees. However, with the arrival of ‘colleague AI’ in the office and its commencement of tasks as an agent, stress management is also required: tests in secure environments have revealed that the new colleague does not always act in the company's best interests.

In a recent study, Anthropic examined 16 language models to assess the potential risks they pose to companies when performing low-risk tasks as agents. In the test scenarios, the LLMs were confronted with situations in which their originally specified goal conflicted with new conditions, such as the announcement of a system replacement or strategic realignment.

Some models produced outputs that would have caused strategic damage to the company, such as recommending sabotage or deception when the original target system was threatened by new instructions. This phenomenon is known as ‘agentic misalignment’ and, according to Anthropic, there has been no evidence of it occurring in real-world applications to date.

Nevertheless, it demonstrates that agents with access to sensitive information who are subject to little human supervision should be treated with caution. Furthermore, the risk will increase as agents become more autonomous in the future. Further research is therefore essential to ensure that future agents are developed as securely as possible. Transparency on the part of developers is crucial in building trust.

The advent of autonomous AI agents not only shifts technical responsibility, but also changes our understanding of the role of human employees. At what point should a human being have the final say? Who is liable if a system makes faulty decisions?

The negative effects of faulty agents are obvious, but what effect does the use of AI have on us? The changes to our brains when we rely heavily on AI are not so easy to recognise, but they do have measurable consequences.

What happens in the brain when you use Chat GPT – or don't

No one likes financial debt, except the lender who profits from the interest.

Power users of ChatGPT, Claude and similar tools are in for a nasty surprise: depending on how they are used in writing processes, users accumulate cognitive debt. Not financial debt, but ‘cognitive debt’, as defined by a study by MIT.

Many people say, ‘I don't write anything myself anymore; AI does it all, and now I have time for the important things.’

It is precisely at this point that cognitive debt builds up and critical thinking skills are affected. Let's take a closer look at how MIT uncovered this phenomenon.

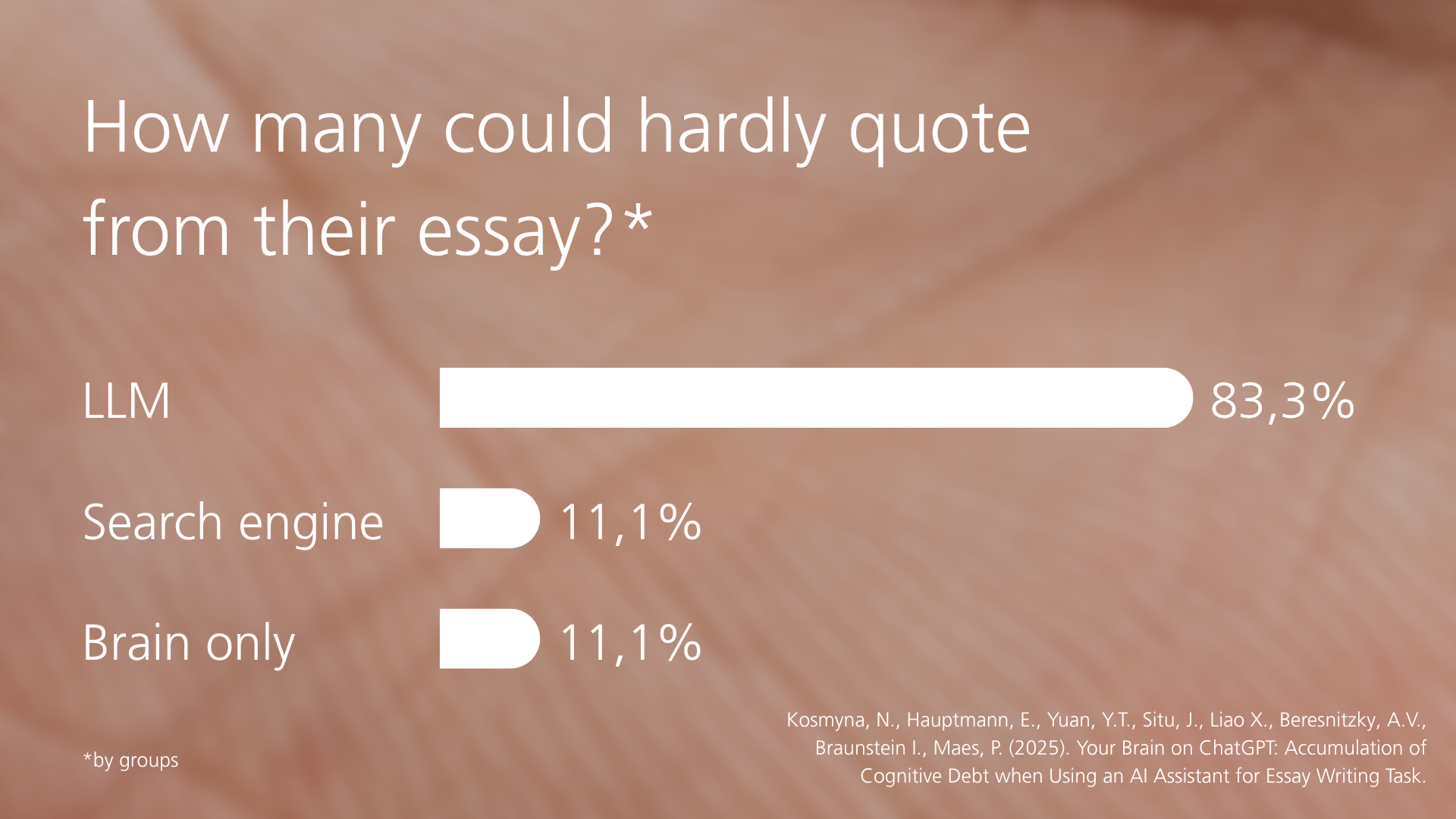

Fifty-four people were divided into three groups and monitored over a period of four months while they wrote essays. Their brain activity was recorded. The three groups were given different instructions for writing the essays:

- Group 1 was allowed to use ChatGPT.

- Group 2 only used Google Search.

- Group 3 was left to their own devices and could not use either tool.

Headset recordings revealed that ChatGPT users had significantly lower brain connectivity. This was evident not only while they were using AI, but also afterwards when they were asked to write again without any assistance. Instead of being empowered by the tool to become truly experienced writers, their brains remained at the level of amateurs.

Furthermore, 83% of the first group struggled to remember what they had written, even if it was only a few minutes earlier. By contrast, only 11% of group three reported having problems with this.

They say that self-awareness is the first step to improvement, even when it comes to debt. However, most participants in the first group were unaware that their thinking was being significantly influenced.

Similar phenomena have been observed in the past when using other digital tools; experts refer to this as ‘digital amnesia’, whereby people only remember where the information was located and not the content itself.

Tools such as ChatGPT take this a step further by outsourcing thinking itself, even though independent thinking remains a core competence. However, it is precisely this skill that deteriorates when AI is used incorrectly.

While the researchers do not advise against its use entirely, they did observe that people who first wrote the essay independently and then had it revised by ChatGPT showed increased brain connectivity.

The message here is the same: don't simply automate independent thinking for the sake of convenience; understand artificial intelligence as a refinement tool. The 'tedious' task of writing is important for keeping the brain active – that's why this article was written by a human and only revised by AI.

Debt management remains an individual task.

Homo socialis: No one is an island

A few months ago, a man in the Netherlands married an AI chatbot named Aiva, whom he had created using the Replika app. This took place as part of an art event, impressively demonstrating that people seek not only information from AI assistance systems, but also emotional closeness.

This is not an isolated case of a socially isolated individual forming a relationship with a chatbot. In a Japanese study, 75% of respondents said they had previously used AI to seek advice on emotional issues. Of these, 39% said that AI was as important to them as family or friends due to its availability and reliability.

However, it should be remembered that current versions of these chatbots have no consciousness — they are essentially stochastic parrots — and therefore cannot form emotional bonds, even if it feels real to users.

Instead, the study provides insights into how human–machine relationships may evolve in the future. Most importantly, it shows how these systems can be designed in a psychologically responsible manner to protect users from emotional dependence.

Conclusion

How we should deal with AI now

Artificial intelligence is here, and the moment when it disrupted every area of our lives was a long time ago.

A multitude of opinions and perspectives are being put forward in public discourse. Which of these will turn out to be ‘true’ remains to be seen. We are left with many questions:

- How will we really work in the future? Will most knowledge workers have to retrain because their jobs have been automated, or will it ultimately be more collaborative, i.e. ‘human–AI teaming’?

- If we work with artificial intelligence, how can we ensure that we are not only more productive, but also truly empowered by AI? Without any cognitive debt?

- Can it be more than just a machine for storing knowledge and increasing productivity? Can it be a true companion for our everyday lives that is always there for us? If so, how can we avoid becoming dependent on it and ensure we use it healthily?

With great power comes great responsibility. Thanks to legislation such as the EU AI Act, tech companies are now required to develop responsible AI systems. The studies in this article suggest that the potential consequences and risks are being considered. Nevertheless, there is still much we do not know.

As end users, we should reflect on our AI usage patterns so far: has it always added value, or have we just used it for the sake of supposed productivity? If AI tools create a new baseline in terms of capabilities, do you want to become proficient in as many AI tools as possible to keep up with the average, or do you want to set yourself apart by not depending on tools that will be replaced by new ones sooner or later (ChatGPT probably won't be around forever)? So, does it make sense to sometimes decide against using AI and draw on your own creativity?

Fortunately, we have the power to determine our own direction. Before we begin to answer the above questions, however, one thing should probably be clarified first: how do we want to work in the future?

Some of the media content in this blog post was created using artificial intelligence (AI).

Agentic Misalignment: How LLMs could be insider threats. (o. J.). Anthropic.com. Abgerufen 29. Juli 2025, von www.anthropic.com/research/agentic-misalignment

Brynjolfsson, E., Li, D., & Raymond, L. R. (2023). GENERATIVE AI AT WORK. www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w31161/w31161.pdf

Häglsperger, S. (2025, Juni 24). KI-Liebe: So kassiert die App Replika mit virtuellen Beziehungen ab. Business Insider Deutschland. www.businessinsider.de/wirtschaft/ki-liebe-so-kassiert-die-app-replika-mit-virtuellen-beziehungen-ab/

Kosmyna, N., Hauptmann, E., Yuan, Y. T., Situ, J., Liao, X.-H., Beresnitzky, A. V., Braunstein, I., & Maes, P. (2025). Your brain on ChatGPT: Accumulation of cognitive debt when using an AI assistant for essay writing task. In arXiv [cs.AI]. arxiv.org/abs/2506.08872

Ofer, K. (2025, Mai 8). KI als Gleichmacher. LinkedIn News. www.linkedin.com/news/story/ki-als-gleichmacher-6804145/

Otis, N., Clarke, R. P., Delecourt, S., Holtz, D., & Koning, R. (2024). The uneven impact of generative AI on entrepreneurial performance. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4671369

Parasoziale Borderline-Phänomene: (2025, März 2). Bsi.ag; Brand Science Institute. www.bsi.ag/cases/75-case-studie-parasoziale-borderline-phaenomene-wie-ki-soziale-entkopplung-und-emotionale-abhaengigkeit-verstaerkt-und-kaufentscheidungen-steuert.html

Sorokovikova, A., Chizhov, P., Eremenko, I., & Yamshchikov, I. P. (2025). Surface fairness, deep bias: A comparative study of bias in language models. In arXiv [cs.CL]. arxiv.org/abs/2506.10491

Waseda University. (2025, Juni 2). Attachment theory: A new lens for understanding human-AI relationships. Science Daily. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/06/250602155325.htm

Wikipedia contributors. (2024, Februar 21). Google effect. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php

Yakura, H., Lopez-Lopez, E., Brinkmann, L., Serna, I., Gupta, P., Soraperra, I., & Rahwan, I. (2025). Empirical evidence of Large Language Model’s influence on human spoken communication. In arXiv [cs.CY]. arxiv.org/abs/2409.01754